Why Mountain Environments Boost Learning In Children

Mountain settings boost children’s attention and working memory—use daily 30–60 min outdoor blocks to improve focus, cognition and wellbeing.

Mountain settings improve children’s learning

Mountain settings improve children’s learning by restoring directed attention, boosting working memory, and cutting stress. They do this through easy natural stimulation, steady physical activity, cleaner air, and quieter surroundings. We recommend programs schedule repeated 30–60 minute outdoor blocks. Mix varied natural features with active play and reflection, and monitor dose and safety. These steps produce measurable cognitive, social, and physiological gains.

Key Takeaways

- Attention & working memory: Mountain exposure restores attention and boosts working memory. A single ~50-minute nature walk can raise post-walk working-memory scores by roughly 20% versus an urban walk in comparable studies.

- Dose guidance: Include one sustained 30–60 minute outdoor attention block. Add daily moderate-to-vigorous activity, about 60 minutes total. Schedule frequent short micro-breaks of 5–10 minutes to lift mood.

- Physiological benefits: Cleaner air, reduced noise, and lower physiological stress (cortisol, heart rate, inflammation) occur in mountain settings. These conditions support prefrontal function, self-control, and classroom readiness.

- Hands-on learning: Place-based mountain activities (orienteering, stream measurement, dendrochronology) strengthen executive skills, spatial and quantitative reasoning, confidence, and social-emotional regulation.

- Implementation & evaluation: Choose varied natural features. Use clear supervision and altitude and weather plans. Track simple metrics—attention tasks, attendance, activity minutes, and teacher logs—to measure impact.

How to implement

Scheduling and dose

- Sustained attention block: Schedule at least one 30–60 minute uninterrupted outdoor session focused on exploration and low-stimulation observation each program day.

- Daily activity target: Ensure children accumulate ~60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity across the day, including active play in mountain terrain.

- Micro-breaks: Insert multiple 5–10 minute outdoor micro-breaks to improve mood and reset attention.

- Varied natural features: Rotate settings—forests, meadows, streams, rocky slopes—to provide diverse stimuli that support different cognitive and motor skills.

- Balance active play and reflection: Combine hands-on tasks with quiet, guided reflection to consolidate learning and enhance working memory benefits.

Safety, supervision, and measurement

- Safety plans: Prepare altitude, weather, and emergency procedures. Use appropriate child-to-supervisor ratios and clear boundaries for each outdoor area.

- Equipment & access: Ensure proper footwear, water, sun protection, and first-aid access. Account for accessibility needs.

- Simple metrics to track:

- Attention tasks: Brief pre/post attention or working-memory checks.

- Attendance & engagement: Daily attendance and teacher-rated engagement logs.

- Activity minutes: Totals of moderate-to-vigorous activity per child.

- Physiological proxies: Optional—heart-rate summaries or simple stress surveys if feasible.

- Iterate: Use collected data to adjust dose, activity mix, and supervision for maximal benefit and safety.

Conclusion

Integrating mountain-based outdoor blocks, structured active learning, and simple monitoring yields clear gains in attention, working memory, stress reduction, and overall classroom readiness. With thoughtful safety planning and routine measurement, programs can reliably translate those environmental advantages into measurable educational outcomes.

Cognitive gains: attention, working memory and the attention-restoration effect

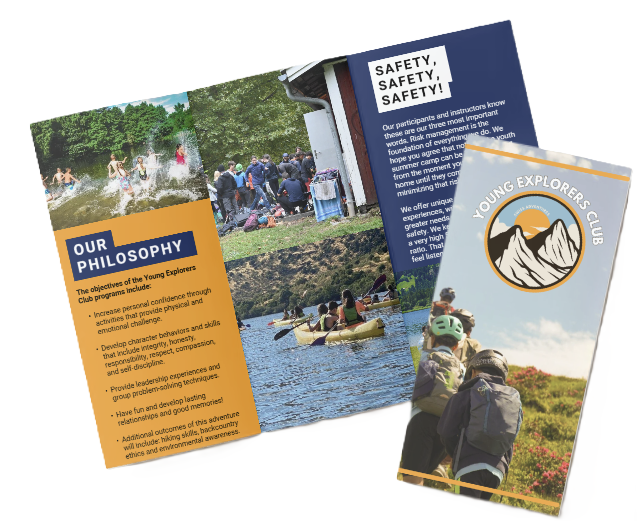

At the Young Explorers Club we’ve seen clear cognitive shifts when children spend time in mountain settings. Short exposure to natural scenes boosts sustained attention and working memory. Berman et al., 2008 reported about a ~20% improvement in working memory after a 50-minute nature walk compared with an urban walk, and that effect maps onto what I observe in mountain classrooms.

I explain the mechanism with Attention Restoration Theory. Attention Restoration Theory proposes that natural settings offer “soft fascination” — low-effort sensory input like birdsong, flowing water and shifting light — that lets directed attention recover from fatigue. In practice, that means shorter lessons followed by 30–50 minute outdoor blocks produce measurable gains in focus.

Case study — working-memory bar-chart (description)

- Chart layout: two paired bars for Nature walk vs Urban walk, each with pre- and post-walk working-memory span.

- Nature walk (50 min): post ≈ pre + ~20% (label: +~20%).

- Urban walk (50 min): post ≈ pre (label: ~0% change).

Caption: Berman et al., 2008 — cognitive benefits (working memory) after a 50-minute nature walk; reported ~20% improvement compared with an urban walk.

Classroom scenario that demonstrates attention restoration

- BEFORE: After a long indoor lesson students show more errors and a shorter span on a 15-minute attention task.

- AFTER: Following a 30–50 minute outdoor session with low-demand natural stimulation, average attention-task scores increase — fewer errors, longer sustained focus — reflecting restored directed attention capacity.

Kuo & Taylor (ADHD) findings and caveats

We draw practical inferences from Kuo & Taylor, 2004, where the same children played in green versus built outdoor settings. The within-subjects comparison showed reduced ADHD symptoms after green-play sessions: inattentive and impulsive behaviours declined relative to built settings. These results are strong for setting contrasts, but they don’t prove a single causal mechanism. Likely contributors include attention restoration, increased physical activity and stress reduction.

How this changes practice (quick, actionable points)

- Schedule 30–50 minute outdoor blocks after intensive indoor work — restores directed attention (Attention Restoration Theory).

- Prefer varied natural features (trees, water, birds) over flat, paved areas — boosts soft fascination and engagement.

- Use brief guided reflection outdoors (2–3 minutes) to focus attention before returning indoors — consolidates gains in working memory.

- Rotate activity types: calm observation, low-intensity movement, and short problem-solving games — combines attention restoration with beneficial physical activity.

- When working with kids showing attentional challenges, plan repeated green-play sessions rather than singular exposures — Kuo & Taylor, 2004 showed setting effects in within-subject contrasts.

I integrate these tactics into our alpine programs and see reliable improvements in attention and working memory across age groups. For more on how outdoor practice supports learning, see our page on outdoor learning.

Physical activity and “dose”: how much outdoor time and movement improve cognition

We, at the young explorers club, align our programming with the WHO recommendation of 60 minutes per day of moderate-to-vigorous activity for children (WHO recommendation). Short bursts outdoors lift mood quickly; sustained outdoor activity produces measurable attention and working-memory gains.

Key evidence and what it means

Meta-analyses report small-to-moderate positive associations between regular moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and executive function and academic performance, with effect sizes commonly in the 0.2–0.5 range (meta-analyses). Mood improvements can appear after just 5–20 minutes outside (Barton & Pretty 2010). Attention and working-memory gains usually require longer contact—typically 20–50+ minutes—to show up on tests (Berman et al., 2008). Mountain settings naturally raise the chance of meeting dose targets: hiking, trail play, skiing and snowshoeing all increase aerobic minutes and encourage free play, which compounds cognitive benefits.

What those effect sizes mean in practice:

- Small effect (~0.2): noticeable gains across weeks to months. Expect modest improvements in on-task behavior and slight test-score upticks.

- Moderate effect (~0.5): clearer behavioral change and measurable gains on standardized assessments.

Comparative classroom scenario: review evidence shows the potential scale of impact. A classroom that integrates 30–60 minutes of outdoor active learning daily can accumulate improvements in executive function and academics in the small-to-moderate range over a semester, compared with indoor-only recess—findings consistent with Donnelly et al., Singh et al.-style reviews.

Practical prescription and monitoring

Use the following mix to hit the dose and amplify cognition:

- Micro-breaks for mood: 5–10 minutes outdoors (walk around schoolyard) — immediate uplift.

- Attention block: one 30–60 minute focused outdoor session daily (walk plus task or outdoor lesson) — target for attention and working-memory gains.

- Regular schedule: 2–5 sessions per week to compound benefits; daily integration (30–60 minutes active outdoor learning) beats sporadic indoor-only breaks.

I recommend tracking minutes each day with simple activity logs or accelerometers and scheduling at least one sustained outdoor block per day where possible. We deliberately build mountain-friendly activities into timetables—hiking, trail play, nature games and seasonal snow sports—to increase moderate-to-vigorous minutes and free-play opportunities. Our approach also leverages unique local features of Swiss nature to make sustained outdoor blocks practical and engaging.

Physiological environment: stress reduction, cleaner air and quieter surroundings

We see clear physiological gains when children spend time in mountain settings. Forest/green exposure — salivary cortisol reductions ~10–20% reported in several studies (Li Q.; Park et al.).

Brief supervised visits commonly drop salivary cortisol in the ~12%–15% range and reduce heart rate while boosting parasympathetic activity (Li Q.; Park et al.). Those shifts lower acute stress and make attention and memory easier to access in learning moments.

Air quality in high-altitude and rural mountain zones often sits much closer to background levels than dense urban areas. WHO: 93% of children globally breathe air exceeding WHO limits (WHO). WHO PM2.5 annual guideline: 5 μg/m3 (WHO). Many cities routinely exceed that threshold, while mountain atmospheres frequently register under 10 μg/m3. Lower noise and lower PM2.5 are linked to better cognitive outcomes — reduced neuroinflammation and improved executive function are expected when pollutants fall.

I summarize the causal chain simply. Less cortisol and lower systemic inflammation lead to improved prefrontal cortex functioning. That translates into better self-control, stronger working memory, and sharper memory consolidation after instruction. In practice, children return to tasks calmer, more receptive, and better at social-emotional regulation.

I recommend short, repeatable outdoor sessions to capture these effects. Sessions of 20–60 minutes produce measurable reductions in cortisol and heart rate and support classroom readiness. We encourage mixing active play with quiet observation so kids get both stimulation and recovery.

Representative PM2.5 ranges (general guidance)

Below are typical, representative ranges so you can compare contexts before planning outings:

- Urban: 20–50+ μg/m3 (many cities exceed WHO guideline).

- Suburban: 10–25 μg/m3.

- Mountain/Rural: near-background, often <10 μg/m3 (closer to WHO guideline).

Take care: valleys and local sources can trap pollution, so local monitoring is useful.

I weave these practices into our programmes and materials. Short, repeated mountain visits combined with quieter, cleaner air conditions deliver physiological advantages that support sustained learning. For research-backed benefits of more outdoor time, see time in nature.

Social, emotional and pedagogical advantages: forest-school evidence and experiential learning

We, at the Young Explorers Club, draw on a strong evidence base showing outdoor programs boost social skills, resilience, motivation and sometimes attainment. Evaluation work in the UK and Scandinavia reports consistent qualitative and quantitative gains in confidence, social interaction and emotional regulation. I stress that effects show up across diverse programs even when numeric gains differ by site and method.

The phrase “Forest school / outdoor learning — measured improvements in social-emotional outcomes and engagement” captures repeated findings. Program reports and local studies often add measurable increases in school engagement and attendance after sustained outdoor sessions. One concise summary is the case-line: “Forest school example — improved social skills & classroom behavior after 6–12 months of weekly outdoor sessions”, which reflects how weekly, long-term exposure changes behaviour and classroom dynamics.

Experiential, place-based and embodied approaches make mountain settings especially effective. Mountains let us run hands-on, multisensory investigations — geology walks, seasonal ecology studies, stream measurements and navigation tasks — that map directly onto curriculum goals. These activities promote experiential learning, place-based education, embodied learning and multisensory learning while engaging attention, memory and executive skills. Practical outdoor tasks encourage teamwork and require on-the-spot risk assessment, which builds emotional regulation and confidence.

Concrete lessons and commonly reported outcomes

Below are mountain-based lesson examples tied to cognitive skills, followed by commonly reported program outcomes.

- Measure stream flow (rate and units): Students time floats, measure distances and compute flow rates. Targets quantitative reasoning, applied measurement and proportional thinking.

- Tree-ring analysis (dendrochronology basics): We count rings and relate widths to wet/dry years. This links history and climate lessons to pattern recognition and temporal reasoning.

- Map-reading and orienteering: Students use contours and compass bearings to navigate. This embodied navigation strengthens spatial working memory and executive planning.

- Rock and mineral ID plus simple field experiments: Hands-on observation and tests (hardness, reaction) sharpen scientific reasoning and attention to detail.

Commonly reported outcomes include:

- Improved confidence

- Better teamwork and peer interaction

- Enhanced risk assessment skills

- Stronger attention and focus

- Greater emotion regulation

- Higher engagement and improved attendance

I recommend linking classroom objectives to outdoor tasks from day one. For practical guidance on structuring sessions that prioritize reflection and skill transfer, see this short primer on outdoor learning.

Emerging biological pathways: biodiversity, microbiome and indirect links to cognition

We, at the Young Explorers Club, track how mountain biodiversity may shape children’s bodies and brains. I outline the emerging science linking exposure to soil, plants and animals with immune development, gut–brain signalling and possible cognitive effects.

Exposure to diverse natural microbiota supports immune maturation and shapes the gut microbiome. Early-life contact with a wide range of environmental microbes is tied to fewer allergies and altered immune markers. I emphasize this as a firm observation rather than proof of cognitive change. I summarize the mechanistic idea with the phrase “Biodiversity → immune modulation and gut–brain axis (emerging evidence)”.

The explanatory concepts most often invoked are clear. Researchers often refer to the ‘Old friends’ / farm-biodiversity hypotheses used as explanatory frameworks to explain why contact with traditional, microbially rich environments primes immune tolerance and reduces inflammatory overreactions. These frameworks give a plausible route from outdoor exposure to physiological states that might favour healthy neurodevelopment.

The causal chain we watch is simple and testable: Increased environmental microbial diversity → altered immune regulation/microbiome → lower systemic inflammation → potentially better neurodevelopment and mental health, which could support cognition. Each arrow in that chain is supported by some data; the full chain linking environment to measurable cognitive gains remains tentative.

I acknowledge where evidence sits today. Microbiome shifts after nature exposure have been documented in both cross-sectional and small intervention studies. Immune markers respond to environmental microbial diversity. Longitudinal or large randomized trials that demonstrate a direct microbiome-to-cognition effect are limited. The idea is promising, but preliminary.

I recommend practical, cautious steps for programmes and parents. Prioritize varied outdoor play in natural settings such as alpine meadows and forest edges. Emphasize safe, unstructured contact with soil, plants and small wildlife rather than over-sanitized play. Monitor emerging literature and avoid claiming microbiome-driven IQ gains until stronger evidence appears. For a quick read on why mountain settings work well as classrooms, see Swiss nature.

What we know vs. what’s emerging

Below I list the current evidence and the questions still open.

- Known: biodiversity exposure reduces some allergies; contact with diverse natural microbiota affects immune markers.

- Emerging: direct cognitive benefits via microbiome-to-brain pathways are plausible but not conclusively established; longitudinal and intervention evidence is limited.

I will stress caution in interpretation. Correlational studies can’t prove directionality. Confounders such as socioeconomic factors, diet and overall activity matter. We should treat microbiome→cognition links as promising but preliminary and keep a skeptical eye on new claims.

Practical takeaways I endorse:

- Create regular, low-risk opportunities for children to touch soil, climb, and explore varied plant communities.

- Avoid unnecessary antiseptics in outdoor play; favour reasonable hygiene paired with natural exposure.

- Pair outdoor programmes with basic health monitoring so any claims remain evidence-based.

Implementation, safety considerations and measuring impact

We, at the Young Explorers Club, build programs so safety and learning go hand in hand. I plan routes and schedules that respect elevation limits and local weather while keeping pedagogy central. Altitude risk increases above ~2,500–3,000 m; we follow acclimatization guidance and the Wilderness Medical Society recommendations, and consult medical guidance for any extended high-elevation stays.

Mountain microclimates can flip from sun to squall in minutes. Prepare for strong UV, cold snaps, sudden wind, and slippery terrain. I build redundancy into plans: extra layers, backup shelter, and clear communication channels for fast extraction when needed. We also ensure hydration and heat-management protocols are explicit before departure.

Practical checklist, safety steps and measurable outcomes

Below are practical items and metrics I use when running school trips and pilots.

- Pre-trip planning essentials:

- Check daytime/nighttime temperatures and forecast; pack layers for sun and cold.

- Sun protection (sunscreen, hats), sunglasses.

- Adequate water and hydration plan.

- First-aid kit and trained personnel; emergency communications (cell/satellite as appropriate).

- Terrain-appropriate footwear and equipment; supervision ratios appropriate to activity risk.

- Altitude plan if > 2,000–2,500 m: gradual ascent, monitor for acute altitude illness, know evacuation procedures; consult medical guidance.

- Core safety practices we enforce on-site:

- Brief all adults and children on weather signals, buddy systems, and check-in cadence.

- Run a short acclimatization window if ascent is planned on day one.

- Log hydration and sun protection use during the day.

- Keep an incident log that includes near-misses to refine future routes.

- Quantitative metrics to collect (baseline & post):

- Standardized attention/executive-function tasks (digit span, Stroop variants).

- Classroom behavior incident counts and teacher-rated attention scales.

- Attendance rates and academic test scores (pre/post).

- Salivary cortisol (research settings) and physical activity minutes (accelerometer or logs).

- Local PM2.5/noise measurements (where feasible).

- Collect baseline & post measures: attention tests, attendance, behavior incidents, academic scores.

- Physical activity: minutes/day (aim 60/min WHO).

- Qualitative measures we combine with numbers:

- Teacher, parent, and child surveys on engagement, confidence, social skills, and perceived well-being.

- Short focus groups after the pilot to capture stories and practical barriers.

Simple before/after evaluation plan for managers and teachers:

- Baseline: collect attendance, two classroom attention measures (e.g., teacher rating + digit span), and one academic test.

- Implementation: run outdoor program for X months. Use a clear dose (daily 30–60 min outdoor block or weekly forest-school sessions).

- Retest: repeat the same measures and compute effect sizes and percent changes; add qualitative notes to explain context.

- Start with a small pilot and scale based on feasibility and early outcomes.

Easy teacher-measured starting metric:

- Begin with teacher-rated attention/behavior incidents (simple weekly log) to spot early signal before investing in salivary cortisol or accelerometry.

I recommend pairing measurement with curriculum that emphasizes active attention and reflection; an outdoor learning block amplifies cognitive gains and gives teachers concrete activities to link to tests. We iterate quickly: pilot, review incident logs, adjust supervision ratios, then expand if outcomes and safety data look good.

Sources

World Health Organization — WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour (2020)

Forest Research — Forest school and outdoor learning (concepts, evaluations and evidence summaries)