How Outdoor Challenges Build Self-esteem

Aim 120 min/week in nature: short walks boost mood, focus (~20% working memory) and raise self‑esteem through green exercise.

Overview

Outdoor challenges raise self‑esteem by offering repeated mastery, social connection, attention restoration, and stress reduction. They increase self‑efficacy and can shift self‑concept. We recommend short, practical doses of nature—about 120 minutes per week—to support well‑being and baseline self‑esteem. A single nature walk can boost working memory by roughly 20%. Structured green exercise and adventure programs yield measurable, small‑to‑moderate gains in self‑esteem. Make tasks progressive, include reflection and debrief, and keep social support strong to turn single wins into lasting confidence.

Mechanisms

Repeated mastery

Repeated, scalable challenges (from easy to harder) give participants multiple opportunities for success, which builds self‑efficacy and strengthens a positive self‑concept.

Social connection

Small, supportive groups provide encouragement, modeling, and feedback—key ingredients for converting achievements into lasting confidence.

Attention restoration and stress reduction

Time in nature helps restore directed attention and reduce physiological stress, which improves cognitive performance and creates a better platform for learning and succeeding at tasks.

Practical recommendations

Dose: Aim for about 120 minutes per week in nature as a practical target to support well‑being and baseline self‑esteem. These minutes can be split across sessions (e.g., two 60‑minute visits or several shorter walks).

Timing: A single restorative nature walk can boost working memory by roughly 20%; schedule these walks before tasks that require concentrated attention.

Program design: Use structured green exercise and adventure formats with repeated sessions—typical effect sizes for self‑esteem gains are around d ≈ 0.4–0.6, so repeat sessions are important for cumulative change.

How to structure challenges

- Grade difficulty—start easy and progressively increase challenge so participants experience repeated mastery.

- Provide clear feedback—immediate, specific feedback helps participants understand progress and learn from setbacks.

- Include reflection and debrief—structured reflection consolidates learning and links achievements to personal capability.

- Keep groups small and supportive—social support magnifies gains and helps sustain motivation.

Key Takeaways

- Aim for about 120 minutes per week in nature as a practical dose to support well‑being and baseline self‑esteem.

- Single nature walks can boost working memory by roughly 20%. Schedule restorative walks before tasks that need concentration.

- Regular green exercise and adventure programs produce small‑to‑moderate self‑esteem gains (typical effect sizes around d ≈ 0.4–0.6). Repeat sessions to build cumulative change.

- Design challenges with graded difficulty, clear feedback, structured reflection, and small supportive groups to convert single successes into lasting self‑efficacy.

- Measure and document—use validated baseline and follow‑up measures, record dose and progression, and note that cohort and observational findings show associations, not definitive causation.

Lead / Hook: Big headline facts to open the post

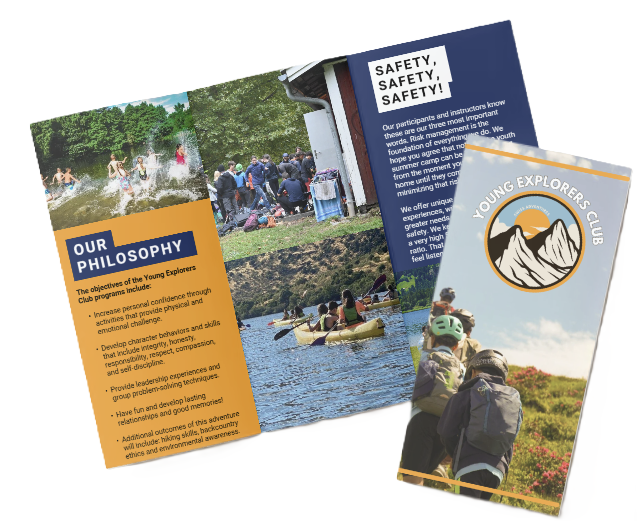

We, at the young explorers club, lead with three hard numbers you can use today. Short exposures to nature change mood, thinking and self‑worth in measurable ways.

A practical nature dose matters: spending at least 120 minutes per week in nature is associated with higher rates of good health and well‑being (White et al., 2019). Treat 120 minutes/week as a target you can schedule across walks, playtime or sessions at camp.

Cognitive gains happen fast. A single walk in nature produced about a 20% gain on a working‑memory task versus an urban walk (Berman, Jonides & Kaplan, 2008). That kind of boost helps kids focus in class and feel more competent during challenges.

Green exercise consistently lifts self‑esteem. Meta‑analytic results show small‑to‑moderate effects (d ≈ 0.4–0.6), so expect a meaningful population‑level gain when physical activity happens outdoors. For perspective, d = 0.5 equals roughly half a standard deviation — a moderate, noticeable improvement in everyday terms.

Key figures — fast facts you can act on:

- Aim for a nature dose of 120 minutes per week (White et al., 2019).

- Expect working memory improvements of about +20% after a nature walk (Berman, Jonides & Kaplan, 2008).

- Green exercise yields a self‑esteem boost with effect sizes around d ≈ 0.4–0.6.

- Interpret d = 0.5 as half a standard deviation — a moderate, population‑level meaningful effect.

We use these facts to shape activities that build confidence quickly. Short, regular outdoor sessions add up. Combining play, guided challenges and movement in green settings multiplies benefits. This approach also confirms why camp frequently builds self-esteem through achievable goals and repeated success.

Evidence: Controlled trials, meta‑analyses and population studies

I lay out the strongest empirical signals linking outdoor challenge and nature exposure to cognitive gains, mood improvements and higher self‑esteem. The evidence spans randomized experiments, multiple meta‑analyses of green exercise and adventure education, plus large population cohorts. I flag numeric takeaways you can use in program design: 120 minutes/week; ~20% working‑memory gain; self‑esteem effect sizes d ≈ 0.4–0.6; and adventure program effects labelled as “small‑to‑moderate”.

Key studies, designs and headline results

Below I list the studies with design and the numeric result you can rely on when planning sessions or evaluating outcomes:

- Berman, Jonides & Kaplan (2008) — randomized/controlled, within‑subject experiment comparing a nature walk to an urban walk. Result: improved mood and working‑memory with about a ~20% working‑memory gain after the nature walk. This provides experimental evidence for short‑term cognitive restoration mechanisms.

- Green exercise reviews (Pretty; Barton & Pretty) — meta‑analytic summaries pooling controlled trials of exercise in natural settings. Result: consistent, moderate improvements in self‑esteem and mood, with representative effect sizes d ≈ 0.4–0.6. These effects are robust across ages and activities.

- White et al. (2019) — large population cohort study. Result: “Spending at least 120 minutes per week in nature is associated with higher rates of good health and well‑being.” Note: observational association ≠ causation; use this as a practical dose target rather than proof of causality.

- Engemann et al. (2019, PNAS) — childhood residential green‑space cohort. Result: greater childhood exposure to green space was linked with reduced risk of multiple psychiatric disorders later in life, with reported relative‑risk reductions reaching notable levels for some diagnoses.

- Hattie et al. (1997) / adventure education meta‑analyses — outward‑bound and adventure programs across studies. Result: measurable improvements in self‑concept and self‑efficacy; effects characterized as small‑to‑moderate.

I present the population findings alongside experimental results like Berman et al. (2008) to support plausible causal pathways: attention restoration, stress reduction and mastery experiences during outdoor challenges.

Practical implications and rapid recommendations

- Treat 120 minutes/week as a program target. Structure sessions so kids accumulate that dose across short daily activities or two longer weekend outings (White et al., 2019).

- Use challenge tasks that create repeated mastery and measurable success. Adventure education shows small‑to‑moderate gains, so stack brief wins to amplify effects (Hattie et al., 1997).

- Build cognitive‑restoration breaks into activity schedules. Simple nature walks can produce ~20% working‑memory improvements (Berman et al., 2008); schedule them before tasks that need focus.

- Monitor change with short, reliable measures. Given meta‑analytic effect sizes around d ≈ 0.4–0.6 for self‑esteem, expect moderate shifts over weeks; plan sample sizes and pre/post measures accordingly.

- Remember observational limits. Use cohort findings (White et al., 2019; Engemann et al., 2019) to justify dose and long‑term goals, and pair them with experimental elements to strengthen causal claims.

We provide camps that emphasize progressive outdoor challenges and measurable achievement; see how camp builds self‑esteem for program examples and activity templates.

Mechanisms: How outdoor challenges build self‑esteem (theory and physiological anchors)

Psychological pathway: challenge → mastery → self‑efficacy → esteem

We structure challenges so kids experience incremental risk and clear feedback. Each solved task becomes a mastery experience, which Bandura identifies as the primary source of self‑efficacy. We sequence tasks so success is attainable but meaningful. That sequencing converts single wins into a growing belief in capability. Domain‑specific gains then spill over into broader self‑esteem. Adventure program evidence shows small‑to‑moderate self‑concept gains after guided expeditions and skill progressions. We also emphasize shared accomplishment; group wins amplify individual confidence. For a practical view on achievement‑focused gains, see our page on self‑esteem through achievement.

Physiological anchors: stress, cognition and social bonding

Below are the key physiological mechanisms we rely on and how they support psychological change:

- Nature lowers physiological stress markers. Studies report reductions in salivary cortisol on the order of ≈10–20% and heart‑rate drops of several beats per minute after brief exposures. Reduced sympathetic arousal lets kids approach subsequent challenges calmer and more focused.

- Cognitive restoration replenishes directed attention. A nature walk has been shown to improve working memory by about 20% (Berman et al.), which boosts problem solving during tasks and helps sustain effort.

- Social bonding from group challenges creates a safety net. Shared effort and mutual praise increase perceived social support, and that social reinforcement multiplies self‑efficacy gains from individual mastery.

We integrate these pathways in practice by pairing graded technical tasks with recovery periods in natural settings, by coaching reflection on specific successes, and by arranging small‑group problem solving so social feedback is immediate. This combination speeds physiological recovery, strengthens working memory, and converts single achievements into lasting self‑esteem.

Types of outdoor challenges and how each maps to self‑esteem outcomes

We classify outdoor challenges by intensity and the psychological mechanisms they trigger. Short, repeated exposures restore mood and concentration quickly; intensive programs build lasting self‑concept through mastery.

Low‑challenge nature exposure (walking, gardening, forest bathing)

Short nature doses produce rapid restoration of attention and mood and help maintain baseline self‑esteem. We recommend a baseline target of about 120 minutes per week in green space to sustain those effects. These activities are low risk and fit daily routines, so they work well for maintenance and recovery days.

- Keep sessions short and regular: 20–30 minutes after school or work preserves gains.

- Add simple achievements: a small garden task or a timed walk raises perceived competence.

- Use sensory anchors: focus on sounds, textures and breath to speed mood benefits.

Green exercise (running, cycling, group hikes)

Exercise in natural settings delivers immediate self‑esteem boosts comparable to indoor exercise, and often larger when done outside. Meta‑analytic evidence reports typical effect sizes around d ≈ 0.4–0.6 for self‑esteem gains from repeated green exercise. We see two useful patterns: single sessions lift mood and confidence quickly; repeated sessions accumulate moderate, measurable improvements in self‑esteem.

- Pair effort with reflection: brief post‑activity check‑ins cement achievement.

- Vary social format: solo runs build autonomy, group hikes add social belonging.

- Schedule consistency: 2–3 sessions per week produce steady cumulative gains.

High‑challenge adventure activities (climbing, ropes courses, multi‑day expeditions)

High‑challenge activities generate strong mastery experiences that translate into measurable increases in self‑concept and self‑efficacy. Program intensity and graduated skill progression matter most. Meta‑analytic reviews characterize these effects as small‑to‑moderate (Hattie et al.), but their real strength lies in how they reshape a participant’s narrative about capability.

- Build a clear progression: skills → supported challenge → independent task.

- Emphasize debrief and meaning‑making after each challenge to link action to identity.

- Keep safety and facilitation tight so psychological gains aren’t undermined by fear.

Structured outdoor therapy / wilderness therapy

Clinical outdoor programs combine therapeutic techniques with challenge and nature exposure and often show improvements in self‑esteem and behavior. Outcomes vary by program intensity, duration and participant selection. We recommend matching program type to clinical goals and screening participants for fit.

- Prefer programs that include structured reflection and measurable goals.

- Look for graduated intensity and competent clinical staff.

- Expect longer programs to produce larger, more durable changes.

Quick comparative guidance

Use the following mappings when planning an intervention or weekly schedule:

- Short nature walks → immediate mood and attention lifts; good for routine maintenance and stress relief.

- Repeated green exercise sessions → moderate cumulative self‑esteem gains (d ≈ 0.4–0.6); schedule for progressive improvement.

- Intensive adventure programs → stronger, longer‑lasting self‑concept changes (small‑to‑moderate effects; Hattie et al.); best for targeted growth and identity shifts.

- Baseline recommendation → aim for roughly 120 minutes per week of nature exposure to preserve baseline well‑being and self‑esteem.

We integrate these approaches at camp because they stack: simple nature time keeps kids regulated, green exercise builds steady confidence, and focused adventure sequences create breakthrough experiences. See how camp builds self-esteem for an example of that progression in practice.

Designing an outdoor challenge program that maximizes self‑esteem gains

We, at the Young Explorers Club, set clear exposure and repetition targets up front. Aim for at least 120 minutes per week in nature as a minimum baseline (White et al., 2019). For interventions, repeat sessions across weeks so gains consolidate—weekly sessions for 6–12 weeks work best.

Structure the program around a clear mastery progression. Break skills into measurable steps and increase difficulty in small increments. Use mastery logs, challenge badges, or skill charts so progress is visible. Visible evidence of improvement signals competence and feeds self‑esteem. Require facilitators to record one concrete observable skill per session (for example: “knots: 3/5; belay competency: supervised”).

Keep groups small and socially supportive. Small cohorts of 4–8 participants maximize peer encouragement and shared accomplishment. Adventure education literature supports group-based gains, and smaller groups let facilitators tailor challenges and deliver immediate feedback.

Prioritize safety, staffing, and measurement checkpoints. Use trained facilitators for higher‑risk activities and apply conservative risk management. Schedule measurement checkpoints after session 1, at mid‑point, and at program end, then run a suggested follow‑up at three months. Use the Rosenberg Self‑Esteem Scale (RSES) for adults and age‑appropriate validated scales for children. Collect baseline and post measures every time you run the program.

Sample 8‑week program template and documentation checklist

Below is a practical template you can adopt and the items you must document for reliable evaluation.

- Weeks 1–2: orientation, basic skills, trust-building activities, baseline measurement.

- Weeks 3–6: escalating challenges with graded difficulty and repeated practice. Mid‑point measurement at week 4.

- Weeks 7–8: consolidation, reflection, visible demonstration of mastery, post‑program measurement.

- Total exposure: 8 weekly sessions × 2 hours = 16 hours total (meets the 120 min/week guideline when delivered weekly).

- Follow‑up: one contact or booster activity at 3 months with follow-up measurement.

Document all of the following for each cohort:

- Baseline and post measures (RSES or age-appropriate scale), participant logs, and qualitative reflections;

- Instructor-to-participant ratio and staff qualifications;

- Session duration and exact progression steps for each participant;

- Incident logs and risk-management notes;

- Attendance and dose (minutes in nature per week).

I recommend using short, standardized forms for the mastery log and a simple digital dashboard for progress badges. That speeds reporting and helps facilitators spot stalled learners early.

Make measurement useful, not burdensome. Keep surveys short and pair them with a one‑minute reflective prompt after each session. Combine quantitative scores with a single qualitative question like “What did you manage today that surprised you?” to capture meaningful shifts in self‑perception.

We embed reflection and celebration into every program. End sessions with peer recognition and a tangible record of the week’s wins. Visible artifacts—badges, photos, short written achievements—anchor progress in memory and increase the likelihood of sustained self‑esteem gains. builds self-esteem

Measurement, age/population considerations, and limitations to communicate honestly

We use validated instruments and transparent reporting to make claims credible. For adults I rely on the Rosenberg Self‑Esteem Scale (RSES). For younger groups I use the Self‑Perception Profile for Children/Adolescents. I also include the General Self‑Efficacy Scale, mood measures like PANAS, depression screens (PHQ‑9), and life‑satisfaction scales when relevant.

We stress clear reporting. Below I give a compact format you can copy into articles or program reports.

Measures, reporting format, effect sizes, and caveats

Here are the specifics I include in every report:

- Standard measures: RSES; Self‑Perception Profile (children/adolescents); General Self‑Efficacy; PANAS; PHQ‑9; life satisfaction scales.

- Example reporting line you can paste: “RSES: baseline M=18.2 (SD=4.5), post M=21.3 (SD=4.2), mean change +3.1 (Cohen’s d = 0.69), p < 0.01, n = 60, 3‑month follow‑up.”

- Reporting checklist: provide Cohen’s d, percent change, p‑values, sample size, and follow‑up length. Whenever possible report confidence intervals for effect sizes.

- Effect‑size interpretation: d = 0.2 small, d = 0.5 moderate, d = 0.8 large. Typical green exercise and adventure literature reports range roughly d ≈ 0.2–0.8, median around d ≈ 0.4–0.5.

- Heterogeneity note: report variability in effect sizes across subgroups and program doses.

We adapt instruments by age and population. With children and adolescents I insist on age‑appropriate tools and on measures of self‑concept and leadership tied to the program curriculum. For adults I pair RSES with mood measures to capture short‑term and sustained benefits from green exercise. For clinical populations I document program intensity, selection criteria, and concurrent therapies; wilderness or adventure therapy can show gains, but results differ by how participants were chosen and how intensive the intervention was.

We acknowledge key limitations candidly.

- Observational studies—such as White et al. and Engemann et al.—show associations, not causation; people who choose nature may differ systematically.

- Effect sizes vary with program length, intensity, sample, and measurement timing.

- Publication bias and sample‑selection effects can inflate apparent benefits.

We always include a clear “What this evidence doesn’t show” statement. Label population risk reductions as relative risks or hazard ratios and show confidence intervals where available.

For practical examples of how camp strengthens confidence on the ground, see how camp builds self‑esteem in our programs.

Sources

Psychological Science — The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature

ResearchGate — The mental and physical health outcomes of green exercise (Pretty et al.)

NHS — Green exercise explained

ERIC / Review of Educational Research — Adventure education (Hattie, Marsh, Neill & Richards, 1997)