Overcoming Fears: How Camp Challenges Help Kids Grow

Young Explorers Club camps use graduated exposure, peer modeling and mastery to build kids’ confidence, resilience and self-efficacy.

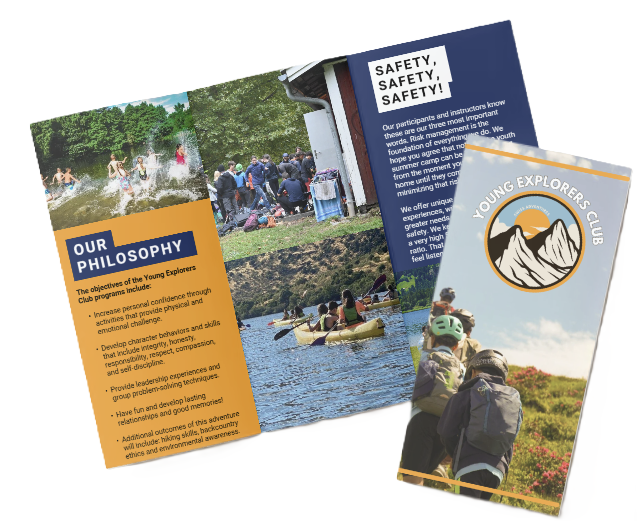

Young Explorers Club

We’re the Young Explorers Club, and we turn fear into competence by combining graduated exposure, repeated mastery experiences, and intentional peer modeling. Children face manageable steps. They build measurable wins and rehearse coping strategies. This structured, low-to-moderate practice drives small-to-moderate gains in self-efficacy and resilience. Those gains often carry over to school, social settings, and home when programs use clear progress markers and firm safety protocols.

Key Takeaways

- Graduated exposure — breaking challenges into short, predictable steps cuts avoidance and lowers physiological threat responses.

- Mastery experiences (including skill practice, measurable wins, and timely encouragement) boost self-efficacy and keep children engaged.

- Peer modeling and cooperative tasks speed learning by showing success is doable and by reducing perceived risk.

- Practical elements — scaffolded progressions, micro-goals, repetition across varied contexts, debriefs, and parent updates — help transfer gains back to daily life.

- Camps can scale exposure-based practice responsibly, but they must pair programs with trained staff, clear safety protocols, routine measurement, and clinical referral pathways when needed. We train staff and maintain strict safety checks to protect progress and confidence.

Mechanisms

We, at the Young Explorers Club, structure camp to turn fear into skill through gradual, supported practice. Camps lower avoidance and increase willingness to try by giving kids repeated, safe encounters with manageable challenges. That combination builds confidence and independence over days and weeks.

How camp reduces fear — key mechanisms

Below are the core processes I use at camp to help kids move from anxious avoidance to confident action:

- Graduated exposure: I break big fears into small steps so children face the next doable challenge rather than an overwhelming one. This mirrors exposure therapy and reduces anxiety through repeated, predictable practice.

- Social support and peer modeling: Peers and counselors model calm, competent behavior. Seeing others succeed makes a task feel achievable and speeds learning through social learning.

- Mastery experiences: I design tasks so kids experience clear, measurable success. Each win raises self-efficacy and makes the next task feel attainable.

- Reframing risk into challenge: Activities emphasize skill-building over danger. That cognitive shift transforms appraisals of threat into opportunities for growth.

Psychological principles, reach, and practical implications

Exposure works because it reduces avoidance and rewires fear responses; that’s the same principle behind exposure therapy. Bandura’s concept of self-efficacy explains why mastery experiences matter: belief in ability follows success. Peer modeling accelerates change through social learning, and SEL practices amplify emotional regulation and resilience. Camps create repeated, low-to-moderate intensity learning cycles that combine all three mechanisms into a single setting.

The scale matters. Approximately 14 million children and adults attend camps in the U.S. each year (American Camp Association). At the same time, about 1 in 6 U.S. youth aged 6–17 experience a mental health disorder in a given year (CDC). Those numbers show camps can be a high-impact venue for delivering exposure-based practice and social learning to large numbers of young people.

I recommend these practical steps for camps, clinicians, and schools that want to use this model:

- Integrate graduated exposure into activity progressions and document incremental wins so counselors can track mastery.

- Train staff in guided peer modeling and brief SEL techniques so social learning is intentional, not accidental.

- Coordinate with clinicians: camps can provide low-to-moderate intensity exposure that complements outpatient treatment.

- Use simple assessment points (before, mid, after) to measure changes in confidence and avoidance, and share those results with parents and providers.

That sense of success also builds self-esteem, which reinforces resilience and long-term independence. Camps aren’t a replacement for clinical care when a child needs it, but they are a scalable, practical platform where exposure, mastery experiences, and peer modeling come together to create durable behavioral and emotional change.

Overcoming Fears: How Camp Challenges Help Kids Grow

We, at the young explorers club, use graduated exposure to turn fear into competence. I guide campers through repeated, manageable encounters with what scares them so avoidance and anxiety drop with each attempt. Small early wins build momentum. They make kids more willing to try harder elements and stay engaged rather than shut down.

Graduated exposure works because it reduces the intensity of the threat response. I break a big challenge into clear, bite-sized steps. Each step is brief, achievable, and predictable. That predictability matters. It lets campers rehearse coping strategies—breathing, positive self-talk, asking for help—and see those strategies work. Visible progress rewires expectation: uncertainty shifts to confidence.

Self-efficacy grows when campers feel real mastery. I focus on three things at once: skill practice, timely encouragement, and measurable evidence of progress. Skill practice builds competence. Encouragement keeps effort high. Evidence—like improved times, cleaner knots, or successful single-move climbs—gives campers proof they improved. They start to tell themselves they can do hard things. That internal narrative changes behavior more than praise alone.

I combine exposure and mastery with social factors. Peer modeling shows that others have succeeded; that lowers perceived risk. Cooperative tasks let shy kids try next-level skills with teammates supporting them. Staff give clear expectations and immediate, specific feedback so progress doesn’t feel vague.

Practical steps I use with campers

- Scaffolded challenges: I map a path from easiest to hardest and keep each step short.

- Micro-goals: Campers aim for one small, measurable outcome each session.

- Repetition with variety: I repeat key tasks but change context so skills generalize.

- Safe failure cycles: I normalize mistakes, debrief quickly, and repeat until mastery improves.

- Peer modeling: I point out classmates who overcame the same fear and how they did it.

- Encouragement scripts: Staff use specific praise—“You tightened your knot faster today,”—not vague compliments.

- Progress markers: I track scores, photos, or short logs so kids see improvement.

- Transition rituals: Small routines before a task reduce anxiety and signal readiness.

- Parent updates: I share concrete wins with families so support continues at home.

I recommend starting with one focused fear and applying these steps consistently for several weeks. For programs that emphasize outdoor play, our use of outdoor challenges accelerates resilience because nature gives varied, low-stakes practice opportunities. Camps that combine graduated exposure and mastery don’t just reduce fear; they build a durable belief in success that carries into school, friendships, and future adventures.

Interpreting Meta-Analytic Effect Sizes and Evidence

We interpret meta-analytic findings as indicating small-to-moderate impacts on self-efficacy and resilience (d ≈ 0.3–0.5). To make that concrete, we use Cohen’s d benchmarks: d = 0.2 equals small, d = 0.5 equals moderate, and d = 0.8 equals large. Across studies, we see consistent patterns: meta-analyses and controlled trials commonly report small-to-moderate gains on self-efficacy, resilience, and related social-emotional outcomes. We caution that many camp and ACA-member surveys report high percentages of camper-reported gains in independence, confidence, and social skills; we treat those as self-report and advise confirming exact percentages, sampling frames, and methods before citing them. Notably, we observe the strongest changes when children face outdoor challenges that push perceived competence and create safe, scaffolded risk.

Presentation guidance for journalists and program leaders

We recommend the following when presenting evidence:

- Display pre/post bar charts of validated scales with error bars; include sample sizes and p-values directly on the figure so readers can judge precision.

- Report effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals alongside p-values; translate d-values into plain language to aid interpretation.

- Explicitly label study design (pre/post single group, waitlist control, randomized) and note follow-up length so readers see durability of effects.

- List common limitations clearly:

- self-selection

- lack of blinding

- short follow-up periods

- reliance on self-report measures

- Provide methodological transparency: share sampling frames, missing-data handling, and whether validated instruments were used.

- When possible, present subgroup analyses and sensitivity checks; show how results change with different analytic choices.

We prioritize clarity over jargon and emphasize that small-to-moderate effect sizes can be meaningful in real-world settings when interventions scale or when multiple small gains compound. We encourage program leaders to pair routine measurement with longer follow-ups and validated tools so we can build a clearer evidence base for how camp challenges help kids grow.

Low-threat Progressive Activities and Challenge Pathways

Low-threat progression: early wins and graduated exposure

We design early activities to give kids small, clear successes that reduce avoidance and build momentum. At the Young Explorers Club we layer team initiatives, low ropes elements, trust falls and problem-solving stations so campers get repeated, low-intensity exposure and quick feedback. Each station targets a single fear: height, peer evaluation, failure, or uncertainty. We coach, encourage peer support, and scale difficulty every time a camper shows readiness.

A few operational points I rely on when running progressions:

- Keep group sizes small for initial attempts so social pressure stays low.

- Give one clear objective per attempt and one specific compliment after each try.

- We use graduated exposure: start on the ground, move to belayed low ropes, then to small heights before asking for a high-ropes attempt.

An anonymized micro-case illustrates a typical arc: Camper A refused to climb at arrival (0 attempts). After progressive low-ropes exposure over three days, they attempted two elements. By day five they completed a high-ropes element with a belay and cheering peers. That timeline shows how small wins compound into readiness for higher exposure.

I link progressions directly to confidence gains; for more on how camp builds self-image through achievement see camp builds self-esteem.

Higher-challenge activities, therapy and social exposure

We introduce higher-challenge activities once a camper has several low-threat successes. These activities provide more intense exposure and clearer mastery opportunities, and are always paired with reflection and support.

Typical higher-challenge activities include:

- High ropes

- Climbing wall sessions

- Zip line runs

- Canoeing/kayaking

- Backpacking or wilderness trips

Each activity is paired with a structured debrief: what worked, what felt hard, and what the camper learned. That debrief is where practice becomes insight.

Structured therapeutic programs combine challenge with coaching. Adventure therapy, wilderness therapy and Outward Bound–style expeditions add therapeutic framing, explicit reflection, and professional facilitation so emotional gains last. We use these formats to move campers from short-term bravery to sustained self-efficacy.

Social challenges offer a parallel pathway. Cabin-group responsibilities, campfire sharing, and leadership roles provide role-based exposure to social fears like public speaking and peer judgment. These risks are repeated and naturalistic, so confidence grows in daily contexts.

To map activity intensity to likely short-term outcomes I use a simple matrix that staff can apply in planning. Below I list the mapping categories and outcomes so teams can choose sequences that fit each camper.

- Low intensity → reduced avoidance: campers make first attempts, show lower physiological distress, and report curiosity.

- Moderate intensity → increased self-efficacy: campers complete multi-step tasks, take small leadership moves, and begin spontaneous volunteering.

- High intensity → visible confidence behaviors: campers lead others, verbalize learning, and generalize courage to new situations.

When mentioning prevalence of specific elements like ropes courses, I don’t assign percentages without checking authoritative listings. Programs should verify figures against ACA directories or regional camp listings before publishing any statistics.

Micro-case Studies: Camp Challenges That Help Kids Overcome Fear

Case A — “11A”

Background: 11-year-old who avoided heights and refused playground climbing.

Baseline measures: GSES = 18/30; observed 0 attempts on the ropes course during the first two days.

Intervention: daily graduated low-ropes practice, peer modeling from a same-age cabin mate, and nightly counselor debriefs.

Outcome: GSES = 23/30 at exit; completed one high-ropes element on Day 9. Quote: “I didn’t think I could do it, but I did.”

Follow-up: parent phone interview at 6 weeks reported volunteering for a school assembly; teacher checklist at 3 months confirmed increased classroom participation (observed raising hand twice per week vs once before).

Case B — “9R”

Background: 9-year-old with social withdrawal and fear of group challenges.

Baseline measures: Social Approach Scale = 12/20; avoided team tasks in the first three activities.

Intervention: scaffolded team tasks starting with paired challenges, graduated to small-group problem-solving, plus counselor prompting and selective encouragement.

Outcome: Social Approach Scale = 16/20 at exit; led a four-person team on Day 7. Quote: “I was nervous, but my team helped me try.”

Follow-up: structured parent survey at 8 weeks showed enrollment in an after-school club; parent log noted first club attendance within two weeks of camp end.

Case C — “13M”

Background: 13-year-old anxious about water and reluctant to try canoeing.

Baseline measures: observed avoidance; Physiological Anxiety Rating (camp observation) = high on the first session.

Intervention: swim skills warm-ups, short canoe shuttles with a peer co-paddler, and post-session debriefs focusing on positive steps.

Outcome: completed a 200m tandem canoe leg on the final day; counselor-rated confidence increased from 2/5 to 4/5. Quote: “It felt scary at first, but I kept going.”

Follow-up: parent email at 10 weeks reported the child signed up for community swim lessons; measurement method: parent confirmation plus swim class registration receipt.

Counselor scaffolding, debriefs and peer modeling

Below are core techniques we use and sample language that worked across cases:

- Task breakdown: divide the challenge into 3–5 bite-sized steps and celebrate each step reached. Example: “Today we’ll try the low beam, then the short bridge.”

- Prompting: use brief, specific prompts rather than lecture. Example: “Take one foot, then the next.”

- Selective encouragement: praise effort and strategy, not just success. Example: “You kept your balance by looking forward — great choice.”

- Peer modeling in action: place a slightly more confident peer beside the camper for the first attempts; that peer demonstrates calm breathing and one successful trial while the camper watches, then the peer spots the camper through their first try.

- Debrief script: three questions — What did you try? What helped? What will you try next? End with a concrete next step and a positive note.

Parent perspective and objective transfer examples appear in each follow-up. We document timing and measurement method (phone interview, teacher checklist, registration receipts) so reported gains move from camp into daily life. The steady progress shown above also links to how camp builds self-esteem through success cycles.

Validated measures and study-design recommendations

We, at the Young Explorers Club, recommend a pre/post design with a 3–6 month follow-up to capture durable change in fear, confidence, and functioning. Test campers at arrival (Day 0), again at departure, and once more at 3 months; include a comparison or waitlist control when feasible to strengthen causal claims.

- Key measures:

- Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

- General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES)

- Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

- Age-appropriate GAD-7 for anxiety symptoms

- Sample size: Aim for N≥50 per group to detect moderate effects.

- Statistics to report: means, SDs, sample sizes, Cohen’s d (effect size), p-values, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

- Transparency: Track and report response rates, attrition, and document whether lost-to-follow-up campers differ from completers.

I report results with transparent statistics and a clear example. For instance:

“Mean GSES increased from 22.1 (pre) to 25.5 (post), a 15% increase; Cohen’s d = 0.45 (moderate).” Pair that statement with sample sizes, p-values, and 95% CIs, and show visual pre/post charts for quick reading. We also integrate qualitative evidence—camper quotes, parental reports, and counselor observations—using thematic analysis and presenting exemplar quotes alongside quantitative findings. Our programming explicitly builds self-esteem, so we use mixed methods to demonstrate how challenges map onto growth.

Reporting checklist

- Pre/post/follow-up timing: Day 0 intake, last-day exit, 3–6 month follow-up.

- Comparison group: concurrent or waitlist control when possible.

- Sample size target: N≥50 per arm for moderate effects.

- Statistics to report: means, SDs, sample sizes, Cohen’s d, p-values, and 95% CIs.

- Transparency: response rates, attrition patterns, and baseline differences for dropouts.

Practical templates and tools

-

Sample Rosenberg items (adaptable):

-

“I feel that I have a number of good qualities.”

-

“On the whole, I am satisfied with myself.”

-

“I feel I do not have much to be proud of.”

-

-

Sample GSES items (adaptable):

-

“I can always manage to solve difficult problems if I try hard enough.”

-

“I can remain calm when facing difficulties because I can rely on my abilities.”

-

“I am confident in my ability to handle unexpected events.”

-

-

Brief SDQ/GAD-7 examples:

-

Two SDQ items (e.g., peer relationship and conduct items).

-

Two age-appropriate GAD-style items about worry and physical anxiety symptoms.

-

-

Consent language (brief):

“Parent/guardian permission: I allow my child to participate in brief surveys about camp experiences. Child assent: I agree to answer questions and can stop at any time.”

-

Study timeline:

-

Day 0 intake: consent, pre-test.

-

Final day exit: post-test.

-

3-month follow-up: online/phone.

-

-

Qualitative collection plan:

Collect 3–5 exemplar camper quotes per theme, 1–2 parental reports per family, and counselor logs; analyze with thematic coding and report exemplar quotes next to quantitative tables.

Safety practices and reporting for camp challenge activities

We, at the Young Explorers Club, run challenge activities with clear safety protocols and active risk management. We require certified instructors and trained facilitation for every element that carries height, water, or technical risk. Staff maintain appropriate facilitator-to-camper ratios, follow written emergency protocols, and deliver activities in progressive steps so campers meet skills before exposure increases.

I outline the core practices we enforce:

- Certified instructors: every high- and low-ropes session, water activity, and technical-skill lesson is led or supervised by staff with verified certifications (for example, high-ropes instructor certification and lifeguard/boat safety where applicable).

- Facilitator-to-camper ratios: we set ratios based on activity complexity and local regulation. Ratios and staffing are recorded before each session.

- Medical screening and waivers: we collect pre-camp medical screening information and signed waivers or consent forms that document known conditions, emergency contacts, and treatment permissions. Waivers are reviewed by leadership and stored securely.

- Safety protocols and progressive introduction: activities follow stepwise progressions — demonstration, coached practice, then full challenge. We use protective equipment and checklists for every setup.

- Emergency protocols: on-site first aid, clear communication plans, and defined transfer routes to the nearest medical facility form the backbone of our response plan. We run drills to keep response times sharp.

We track incident data to learn and improve. Reporting goes beyond raw counts. We log injuries and serious incidents with context and standardized denominators (for example, incidents per 1,000 participant-days) and compare those rates to baseline norms for youth activities. If we ever publish specific incident rates we pull the exact figures from authoritative sources such as ACA safety reports or relevant state health department data and place the source and year in captions.

Limits exist for challenge programming. Camp-based exposure can build confidence and reduce everyday fear responses, but it isn’t a substitute for clinical treatment for severe anxiety disorders. We partner with mental-health professionals when campers present significant clinical needs and maintain clear referral pathways to therapists and pediatric providers. Staff get training to recognize when a child needs professional assessment and we document referrals.

Editor checklist: safety facts to verify

- Typical facilitator-to-camper ratios: low-ropes 1:8–1:12; high-ropes 1:4–1:8 (confirm local regulation).

- Required certifications: high-ropes instructor certification, lifeguard/boat safety, first-aid/CPR, plus any regional credentials.

- Common waiver/consent items: emergency contact, medical history, treatment consent, activity-specific acknowledgment of risks.

- Emergency response plans: on-site first aid, communication plan, transport plan, nearest medical facility.

- Documentation: verify and caption staff certifications and program protocols before publishing.

I encourage readers to see how camp often builds self-esteem for campers by pairing challenge with support. builds self-esteem

Sources

Below are possible sources to consult (organization — article/report title). Verify the latest publication dates and figures before publication.

- American Camp Association — Benefits of Camp

- American Camp Association — Research & Reports

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — Data & Statistics on Children’s Mental Health

- American Psychological Association — Exposure Therapy

- Journal of Experiential Education — Adventure education and outcomes: Meta-analytic findings and implications for program evaluation (Hattie et al.)

- Journal of Experiential Education — Journal homepage

- Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning — Journal homepage

- Child Trends — Mental health problems among youth (indicator)

- PubMed — A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7

- Measurement Instrument Database for the Social Sciences (MIDSS) — General Self‑Efficacy Scale (GSE)

- Fetzer Institute / Self‑Measures Collection — Rosenberg Self‑Esteem Scale (RSES) (PDF)