Why Kids Need More Time In Nature (backed By Research)

Boost kids’ health: daily 20-60 min outdoor time improves mental health, attention, MVPA, sleep, and lowers obesity and psychiatric risk.

Children’s Decline in Outdoor Time and Health Impacts

Children now spend far less time outdoors than public-health guidelines recommend. Only about 24% meet the WHO target of 60 minutes/day of moderate-to-vigorous activity. Recreational screen time has climbed, and childhood obesity affects roughly 18.5% of children. Experimental and longitudinal studies show routine nature exposure—even brief daily sessions—cuts stress and rumination. Those studies also link nature with lower lifetime psychiatric risk, sharper attention and academic performance, and more physical activity. We recommend practical steps like 20–60 minutes of outdoor time daily, greener schoolyards, and equitable access to nearby parks.

Key Takeaways

-

Gap between guidelines and behavior: Many children don’t reach 60 minutes/day of activity, screen time remains high, and obesity rates stay elevated.

-

Mental-health benefits: Randomized trials and cohort studies show brief, regular nature exposure reduces stress and negative thinking and links to substantially lower risk of psychiatric disorders.

-

Cognitive and academic gains: Time in nature restores attention and working memory, reduces ADHD-related attention problems, and greener learning environments correlate with better cognitive and academic outcomes.

-

Physical and physiological benefits: Outdoor play reliably increases moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. It also supports sleep and vitamin D production. Short-term physiological studies report lower cortisol and reduced blood pressure.

-

Practical actions: Daily doses of outdoor time (multiple short sessions totaling 20–60 minutes), school and clinician integration (outdoor lessons, expanded recess, Park Rx–style prescriptions), and policy investments to close green-space inequities.

Evidence and Mechanisms

Experimental trials and longitudinal research converge on the conclusion that frequent, even brief, contact with natural environments produces measurable improvements in mental health, cognition, and physical activity. Proposed mechanisms include restoration of attentional resources, reductions in physiological stress markers (like cortisol and blood pressure), increased opportunities for active play, and social and sensory stimulation that reduce rumination and support emotional regulation.

Recommended Practical Steps

-

Daily outdoor time: Aim for multiple short sessions totaling 20–60 minutes each day, adjusted for age, weather, and context.

-

Greener schoolyards: Incorporate trees, natural play elements, and outdoor lessons to support attention and learning.

-

Clinical integration: Encourage clinicians to include Park Rx–style prescriptions or routine counseling about outdoor time during well visits.

-

Equitable access: Invest in parks and safe routes so all neighborhoods have nearby green space.

The Problem: Kids Are Outside Less — The Scale of the Gap

I picture a grandparent who spent whole summer afternoons building forts and biking the neighborhood. I contrast that with a child logging hours on a tablet under artificial light. The difference is striking and measurable.

The gap shows up against clear public-health recommendations. The WHO guideline says children and adolescents (5–17) should do at least “60 minutes/day” of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (WHO). Actual behavior falls far short. In the U.S., “Only 24% meet activity guidelines” (CDC). Childhood obesity is high, too — about “~18.5% childhood obesity prevalence” (CDC, 2017–2020). Screen time helps explain part of the displacement. Common Sense Media (2019) reports average daily recreational screen time of roughly “tweens 4–6 hrs, teens 7+ hrs” (Common Sense Media, 2019). In short: screen time is rising while time outdoors is falling.

I call out three immediate implications for anyone who cares for kids:

- Reduce recreational screen time — set limits and replace passive screens with active options.

- Increase outdoor play — prioritize unstructured and structured outdoor time every day.

- Design realistic schedules — make the 60 minutes/day of activity an achievable part of daily routines.

Key figures that demand action

These numbers make the gap tangible; they also point to where I focus interventions:

- WHO: recommended “60 minutes/day” of moderate-to-vigorous activity for ages 5–17 (WHO).

- CDC: “Only 24% meet activity guidelines” in the U.S. (CDC).

- CDC: “~18.5% childhood obesity prevalence” (CDC, 2017–2020).

- Common Sense Media: recreational screen time averages “tweens 4–6 hrs, teens 7+ hrs” (Common Sense Media, 2019).

I use those figures to prioritize practical shifts: reduce recreational screen time, increase outdoor play, and design schedules that make 60 minutes of activity realistic. Small changes matter. I often recommend simple outdoor routines and family options like family activities that replace even one hour of screens with active time.

Mental Health and Risk Reduction: Nature’s Strongest Evidence

I focus on the studies that make the clearest case: experiments showing immediate benefits and large cohorts showing reduced lifetime risk. The findings converge. They show that nature exposure reduces stress and negative thinking, and improves mood in ways that matter clinically.

Key studies that change how I think about outdoor time

Below are the most convincing results and what they imply.

- Bratman et al. (2015) PNAS — In a controlled walk study, participants who walked in a natural setting reported immediate reductions in “reduced rumination” and showed corresponding neural changes, specifically “reduced activity in subgenual prefrontal cortex” (a brain region linked to depressive rumination). This experimental design supports a causal link between brief nature exposure and drops in negative repetitive thinking.

- Engemann et al. (2019) PNAS — Large-cohort evidence shows that children who grew up with the most green space had up to 55% lower risk of psychiatric disorders compared to those with the least green space. That’s a population-level protective effect across development.

- Meta-analyses and reviews — Multiple syntheses report consistent moderate effects linking greenspace exposure with improved mental health outcomes. These effects are meaningful in size — not tiny changes — and align with small-to-moderate effects seen in some psychological interventions.

Practical implications for parents, educators, and planners

I translate the evidence into actions you can take immediately and policies worth pushing for.

- Prioritize frequent, real-world contact with nature. Experimental walk studies show even short exposure reduces rumination and improves mood, so regular visits to parks or green schoolyards will pay off.

- Make unstructured outdoor play part of routine. Kids process emotions and test coping skills when they play freely in natural settings. I recommend consistent, repeated exposure rather than one-off outings.

- Advocate for more green space in child environments. The Engemann et al. (2019) PNAS finding implies urban planning and schoolyard greening are preventive mental-health measures.

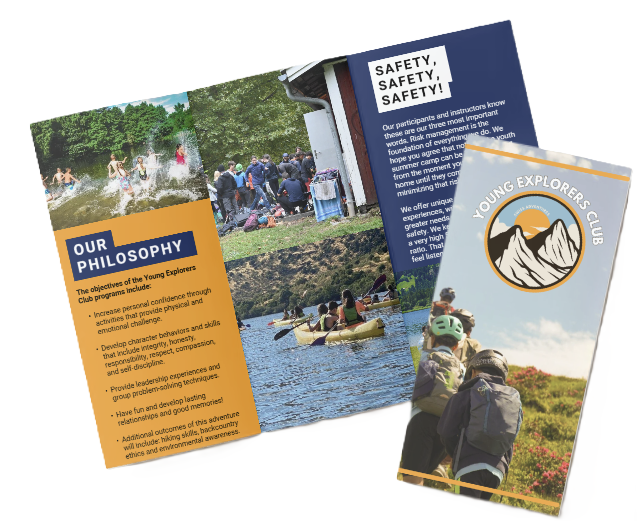

- Use organized outdoor programs to scale exposure. I often point families and educators to options like a first summer camp that emphasizes daily nature time. These programs build sustained habits and social skills alongside exposure.

- Treat nature as a complement to therapy. The size of these effects compares with small-to-moderate psychological interventions, so nature exposure can amplify clinical approaches and act as a low-cost preventive strategy.

I rely on both experimental and longitudinal evidence when I advise parents and institutions. Short-term studies establish likely causality. Long-term cohorts show that exposure during childhood lowers psychiatric risk later on. That combination makes a strong case for making green time a standard part of a child’s life.

Attention, ADHD & Cognitive Function: Better Focus and School Performance

I rely on Attention Restoration Theory (ART) to explain why kids focus better after time outdoors. ART says directed-attention fatigue is replenished by the effortless attention that natural settings evoke, so the brain gets a break without needing conscious control.

What the research shows

- Kuo & Taylor (2004) observed that children with attention symptoms concentrate better after green outdoor activity, suggesting nature can reduce ADHD-related attention problems in real-world settings.

- Berman, Jonides & Kaplan (2008) found improved working memory after a nature walk. Participants scored higher on validated attention and backward digit-span tasks after a park walk compared with an urban walk, indicating short-term restoration of cognitive resources.

- School greening and classroom greening studies, including work by Dadvand et al., link greener learning environments to better cognitive development and improved test performance over time, supporting cumulative academic benefits.

How I translate findings into practice

I focus on repeatable, low-cost actions that fit typical school and family routines. Brief green breaks work well: schedule outdoor lessons, walking transitions, or recess in a nearby park rather than by a busy road.

- Swap a seated indoor activity for a short green activity before demanding tasks or tests for children with attention challenges.

- Add plants to classrooms and advocate for modest school greening projects—they improve air quality and support concentration over weeks and months.

- Use nearby green spaces rather than distant nature reserves to maximize accessibility and routine use.

When I plan programs or advise schools, I prioritize accessibility. Train teachers to integrate outdoor moments into curriculum and assessments so gains are measurable. I encourage parents to include nature-rich activities in daily life and consider sending children to an outdoor-focused program—many families find a short residential option like a summer camp reinforces attention and social skills.

I track outcomes practically: note homework completion and test readiness after outdoor breaks, and collect teacher observations of sustained attention across days. Small, consistent doses of nature produce both immediate improvements in working memory and longer-term boosts in school performance, so I treat outdoor time as essential, not optional.

Physical and Physiological Benefits: Activity, Obesity, Sleep, Vitamin D, and Biomarkers

I emphasize outdoor play because it reliably raises moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) in children and adolescents. Active outdoor play can supply large portions of the WHO 60 minutes/day recommendation. Only about 24% of young people meet that guideline, so time outside matters.

Observational data link regular outdoor activity with lower obesity risk, and U.S. childhood obesity prevalence remains roughly 18.5%. I interpret those figures as a prompt to prioritize free play that gets kids moving, not just structured exercise. I often recommend sessions that let children run, climb, cycle, and invent games; those behaviors drive MVPA more than walk-through programs.

Daylight exposure also has a clear physiological payoff. Bright natural light strengthens daytime circadian signaling, which leads to earlier evening melatonin onset and improved sleep quality and duration. I encourage exposure to morning and afternoon daylight and an evening screen curfew, since excess evening screens blunt melatonin onset and fragment sleep. For practical family ideas that put children in daylight and activity, see family activities and trips that integrate outdoor time.

Sun exposure supports vitamin D synthesis in the skin and can supply up to 80–90% of vitamin D needs with modest daily exposures. I balance that benefit with sun-safety: short, regular exposures on arms and legs often suffice, and I use shade, hats, or sunscreen when exposure would be prolonged. Families who travel or camp can use simple schedules to mix safe sun time with active play—examples live in my suggestions for a first summer camp and broader summer camp guide.

Physiological biomarker studies add another layer. Research on forest bathing (shinrin-yoku) reports reduced cortisol, lower blood pressure, and increased natural killer (NK) cell activity after forest exposure; some immune changes persisted for days to weeks. Those studies are often small and adult-focused, so I treat the child-specific implications as promising physiological evidence rather than definitive proof. Still, the consistent direction of effects supports routine outdoor exposure as a low-risk strategy with physiological benefits. If you want activity-focused destination ideas, explore mountain adventure camps or the best summer camps I recommend.

I find simple prescriptions work best in practice. A single 30–60 minute unstructured outdoor play session can often supply most of a child’s daily MVPA. Frequent short sessions beat one long, forced workout for habitual movement and enjoyment. For families planning trips or weekend time, combining free play with light hikes or outdoor games keeps intensity varied and sustainable—see my notes on family trip in Switzerland and top family activities in Vaud for specifics.

Practical session tips and quick rules I use

- Aim for 30–60 minutes of unstructured outdoor play most days; shorter bursts add up.

- Prioritize daylight windows: morning and late-afternoon light strengthen circadian cues.

- Enforce a 60–90 minute screen curfew before bedtime to protect sleep onset.

- Use short, regular sun exposures for vitamin D, then switch to sun protection if kids stay out longer.

- Mix environments: parks, woodlots, and short forest walks give both activity and the physiological perks seen in forest studies.

- Keep activities child-led; creativity and risk-taking increase MVPA and sustain interest—consider youth leadership and family activities to build habits.

I also recommend eco-aware choices while encouraging outdoor time, so families can pair health gains with low-impact travel and respect for wildlife—read eco travel and wildlife tips for seasonal guidance.

Social, Emotional Development, Proven Models, and Equity

How unstructured nature play shapes social and emotional growth

I see unstructured outdoor play as a primary engine for social learning. Children negotiate roles, solve conflicts, and practice empathy while inventing games and balancing risks. That kind of play boosts creativity and teaches informal risk assessment in a context that feels real but manageable. It also demands self-regulation: kids learn to wait, take turns, and modulate emotions after setbacks. Over time those small episodes add resilience.

The American Academy of Pediatrics highlights the importance of active, unstructured play — including outdoors — for healthy development (American Academy of Pediatrics: importance of play). I use that guidance when advising parents and schools: prioritize free play windows, reduce over-scheduling, and give children safe access to varied outdoor settings.

Practical tweaks work:

- Swap a portion of screen time for daily outdoor play.

- Create loose parts bins for exploration and open-ended construction.

- Let kids lead rough-and-tumble activities within clear safety boundaries to promote physical confidence and social negotiation.

Proven models, documented outcomes, and how to correct inequity

Below are established programs I recommend and why they matter:

- Forest School — child-led, long-term nature immersion that builds confidence, social competence, and cooperative skills.

- Nature Preschool — blends emergent curriculum with outdoor time to foster creativity and early self-regulation.

- Green Schoolyard / Green Schoolyards Program — converts asphalt yards into diverse habitats that increase prosocial play and often higher MVPA during recess.

- Park Prescription / ParkRx initiatives — clinicians encourage outdoor time as preventive care and community health promotion.

- Outdoor Classroom Day — a simple, scalable practice that improves engagement and can support academic focus.

Research links these approaches with gains in social competence, prosocial behavior, creativity, and physical activity during school hours. Some studies also report improved attention and academic outcomes in settings that consistently use outdoor, play-based curricula.

Equity decides who benefits. Green space inequity and “park deserts” mean access to safe, quality green space varies by neighborhood, socioeconomic status, and race/ethnicity. Nature inequity contributes to health disparities: less green space = higher risks for stress-related and cardio-metabolic outcomes. Children in lower-income and many minority neighborhoods frequently face fewer nearby parks and higher environmental hazards, which compounds disadvantage.

I push for environmental-justice–oriented investments that make nature play universal. Effective steps include targeted park creation, safe routes to green spaces, school greening projects, and clinician-led ParkRx referrals tied to local improvements. Schools and community groups can start small: add shade trees, create natural play elements, and schedule daily outdoor classes. For families looking for inspiration and activities that work across landscapes, see family activities that fit outdoor holidays and everyday play.

How Much Nature, Practical Recommendations, Barriers, Measurement, and Policy Actions

I recommend treating nature exposure as a daily health prescription. Aim to fold time outside into the WHO 60 minutes/day MVPA target so activity and green exposure count together. Evidence shows mental-health gains after as little as 10–20 minutes outside, with broader benefits across 20–60 minutes per day; multiple short sessions (15–30 minutes) work especially well for toddlers and preschoolers.

Practical prescriptions and dose guidance

Follow these practical prescriptions I use with families, schools, and clinicians:

- Parents: target at least one 30–60 minute outdoor play block each day plus a short morning or after‑school outdoor moment. For toddlers and preschoolers, schedule multiple short sessions of 15–30 minutes or more.

- Schools: add 20–40 minutes of outdoor learning or recess daily and run at least one class outdoors each week; invest in green schoolyards to make outdoor time routine.

- Clinicians: incorporate a Park Rx during well-child visits and counseling; give families concrete minutes/outdoor goals and local options.

- Session format: combine free play, active games (to boost MVPA minutes), and brief nature-based learning activities. Multiple short bouts across the day often beat a single long one for attention and mood.

- Quick advocacy checkboxes parents can use when talking to schools or clinicians:

- [ ] Ask school to add 20+ min daily recess / outdoor lesson weekly.

- [ ] Request pediatrician to provide a Park Rx for outdoor activity.

- One-sentence template to send to school or clinician:

“Please consider adding regular outdoor time (at least 20–30 minutes daily or a weekly outdoor class) and support access to nearby green space; my child would benefit from school policies that prioritize outdoor play and learning.”

- For ideas to keep daily outdoor time engaging: I point families to resources on family activities and short nature-based routines like this daily outdoor time.

Barriers, measurement, and policy actions

Perceived safety often limits outdoor play. I suggest neighborhood walking groups, supervised nature play, and walking school bus programs to reduce parental anxiety and increase participation. Lack of nearby green space calls for pocket parks, container gardens, tree planting, and green schoolyards to close gaps in access.

Measure change with simple, actionable metrics: minutes outdoors per day, steps/day or MVPA minutes from wearables, sleep duration/quality, a brief mood rating, attention measures, and BMI trends for longer-term monitoring. Use pedometers or consumer wearables, parent logs, teacher observation rubrics (for example SOPLAY-style recess audits), and short validated questionnaires like the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. I recommend trialing a change for 4–8 weeks to detect trends.

Sample tracking row: Day | Minutes outdoors | Steps | Sleep hrs | Mood (1–5) | Notes

Address screen habits by setting curfews and building predictable morning and after‑school outdoor routines. School schedule constraints can be eased by integrating one outdoor lesson weekly and protecting daily recess.

Policy actions I push for are concrete and equitable:

- Require or encourage minimum daily outdoor recess (20 minutes).

- Fund green schoolyards and safe routes to parks and schools.

- Support Park Rx programs and embed nature-based learning in education standards.

- Invest in parks to eliminate park deserts and address green space inequity.

Local advocacy should use keywords like “daily outdoor time”, “Park Rx”, “green schoolyards”, “park deserts”, “green space inequity”, “minutes outdoors”, and “MVPA minutes” when asking officials or school boards to act.

Sources:

World Health Organization (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015128) – “Guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour”

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/children/index.htm) – “How much physical activity do children need?”

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/childhood.html) – “Childhood Obesity Facts”

Common Sense Media (https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/the-common-sense-census-media-use-by-tweens-and-teens-2019) – “The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Tweens and Teens, 2019”

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) (https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1510459112) – “Nature experience reduces rumination and subgenual prefrontal cortex activation” (Bratman et al., 2015)

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) (https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1807504116) – “Residential green space in childhood is associated with lower risk of psychiatric disorders from adolescence into adulthood” (Engemann et al., 2019)

Psychological Science / Association for Psychological Science (https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02168.x) – “The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature” (Berman, Jonides & Kaplan, 2008)

American Journal of Public Health (https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.94.9.1580) – “A Potential Natural Treatment for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Evidence From a National Study” (Kuo & Taylor, 2004)

Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine / Springer (https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12199-006-0072-1) – “Forest bathing enhances human natural killer activity and expression of anti‑cancer proteins” (Li et al.)

Environmental Health Perspectives (https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/10.1289/ehp.1408205) – “Green spaces and cognitive development in primary schoolchildren” (Dadvand et al.)

American Academy of Pediatrics (https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/119/1/182) – “The Importance of Play in Promoting Healthy Child Development and Maintaining Strong Parent‑Child Bonds” (AAP policy statement)

The New England Journal of Medicine (https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra070553) – “Vitamin D Deficiency” (Holick review)

ParkRx / ParkRx.org (https://parkrx.org/) – “Park Prescription / ParkRx” (organizational resource)

Active Living Research / SOPLAY (https://activelivingresearch.org/soplay) – “SOPLAY: System for Observing Play and Leisure Activity in Youth”