Why Outdoor Learning Sticks Better Than Classroom Lessons

Outdoor learning: 120 min/week boosts attention, memory and wellbeing, with short nature breaks plus multisensory lessons driving clear gains.

Outdoor learning restores attention and builds richer multisensory memory traces

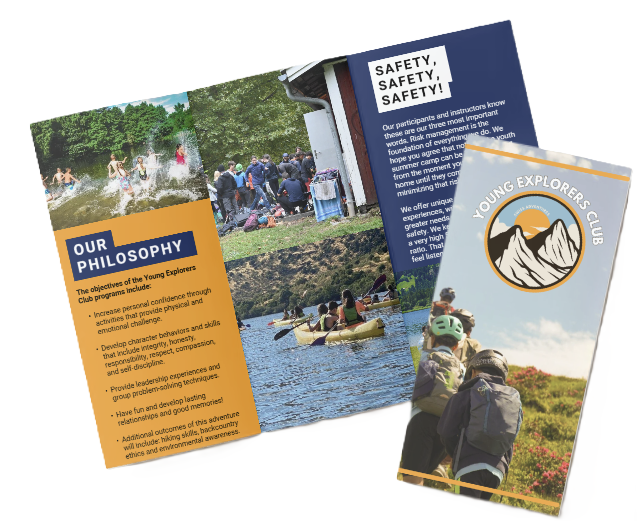

Outdoor learning restores attention and builds richer multisensory memory traces. It boosts immediate focus, working memory and transfer more than prolonged indoor classroom time. We, at the Young Explorers Club, recommend a practical target of at least 120 minutes per week. Split that time into short restorative nature breaks and longer multisensory lessons. Those blocks produce measurable gains in wellbeing, behaviour, physical activity and academic outcomes.

Key Takeaways

- Adopt 120 minutes/week of outdoor learning (for example, two 60‑minute lessons, four 30‑minute sessions, or daily short bursts) and schedule those blocks as non‑negotiable lessons tied to curriculum goals.

- Short 20–30 minute nature breaks restore directed attention quickly (Attention Restoration Theory), while longer outdoor lessons deepen encoding and support transfer.

- Multisensory, active outdoor tasks strengthen encoding and retrieval, improving working memory, recall and application to new problems.

- Outdoor time reduces stress, improves mood and self‑regulation, and increases moderate‑to‑vigorous physical activity (MVPA), which contributes to cognitive and academic gains.

- Pilot changes with baseline and follow‑up measures—topic‑specific tests, wellbeing scales, teacher ratings and activity data—and report sample sizes, effect sizes and limitations.

Scheduling examples

- Two 60‑minute lessons per week focused on curriculum objectives (science, literacy, maths linked to outdoor tasks).

- Four 30‑minute sessions per week combining short practical tasks and reflection.

- Daily short bursts (10–20 minutes) used as restorative attention breaks between indoor lessons.

What to prioritise in lessons

- Multisensory activities—touch, smell, movement and oral discussion to deepen encoding.

- Active learning—problem solving, field investigations and collaborative tasks that require retrieval and application.

- Curriculum alignment—plan outdoor sessions as core lessons, not optional add‑ons, with clear learning outcomes.

Measurement and reporting

- Collect baseline and follow‑up measures: topic‑specific assessments, wellbeing questionnaires, teacher behaviour ratings and activity monitors.

- Report sample sizes, effect sizes and any limitations to support transparent evaluation.

- Use mixed measures—quantitative test scores and qualitative observations—to capture both cognitive and wellbeing impacts.

Recommendation: Start with a small pilot, embed outdoor sessions in the timetable, measure outcomes, then scale up based on evidence. Outdoor learning is a practical, evidence‑informed way to boost attention, memory and broader school outcomes.

Lead: The indoor deficit—and a simple benchmark that fixes it

People in developed nations now spend roughly 90% of their time indoors (EPA/indoor air research). That figure shows up in school life too: long classroom hours, after‑school homework and screen time stack up until students spend most waking hours inside. We, at the young explorers club, see how that steady indoor exposure dulls attention, reduces movement and cuts off the informal learning that happens when kids touch, test and explore.

White et al. (Scientific Reports, 2019) gives a clear counterpoint: spending at least 120 minutes per week in natural settings correlates with higher self‑reported health and wellbeing, with benefits appearing at that 120‑minute mark and above. That threshold is practical. It’s small enough to schedule and large enough to change outcomes.

We at the young explorers club recommend treating 120 minutes per week as the minimum outdoor learning benchmark. That could be two 60‑minute lessons, four 30‑minute sessions, or shorter daily bursts that add up. Adding two hours of structured outdoor activity each week is a deliberate reallocation of time away from screens and classrooms. It’s a simple fix you can measure and defend when planning timetables.

How to hit 120 minutes weekly

Here are practical, classroom-ready ways to reach the benchmark:

- Two 60‑minute outdoor lessons per week that replace one indoor period each time.

- Four 30‑minute sessions spread across core subjects to reinforce experiential learning.

- Short daily blocks: 7×15 minutes plus one 15‑minute nature walk gives 120 minutes.

- Combine outdoor breaks with active learning (science trials, sketching, measurement tasks).

I’ll add a few quick implementation tips. Schedule outdoor blocks as non‑negotiable lessons in the timetable. Link activities to assessment goals so teachers don’t see them as optional. Use nearby green spaces or the schoolyard; access matters more than perfection. Track minutes weekly and share simple metrics with parents and staff to maintain momentum.

For classroom teams looking for evidence and methods, consult our primer on outdoor learning to align pedagogy with the 120‑minute target.

How outdoor exposure restores attention and strengthens memory

How Attention Restoration Theory explains recovery

We rely on Attention Restoration Theory (ART) to explain why nature calms mental fatigue and boosts focus. ART says natural settings replenish depleted directed attention by offering soft, effortless engagement. Below are the specific psychological qualities that make that possible:

- Fascination: scenes and sounds in nature draw attention without effort.

- Being away: a change of context gives mental distance from routine demands.

- Extent: a coherent, rich environment provides a connected field for the mind to explore.

- Compatibility: the setting matches what learners want to do (play, observe, move).

Together these qualities reduce mental fatigue and restore capacity for concentration and cognitive control. Short exposures, even passive ones, can reset attentional resources; longer, active learning in nature compounds that effect.

Evidence, memory mechanisms and classroom advice

Lab and field studies that use pre/post attention tests or randomized exposure consistently find gains after time in nature. Berman et al. (2008) randomized participants to a nature walk or an urban walk and measured working memory with pre/post tests (backward digit span). The nature condition produced significant posttest improvements compared with the urban condition, showing restored working memory after a single walk.

Hands-on outdoor lessons strengthen encoding in ways classrooms rarely match. Multi‑sensory input — sight, sound, touch and movement — creates richer contextual cues. Those cues form stronger memory traces and make retrieval and transfer easier during later tasks. Movement links spatial and procedural information to concepts, which improves recall and supports generalisation across settings.

I apply these findings in two practical ways we recommend for schools and programs. First, use brief ART-style nature breaks of about 20–30 minutes to restore attention during long class blocks. Short, regular breaks cut mental fatigue and improve performance on follow-up tasks. Second, schedule extended multisensory outdoor lessons when you want deep encoding and transfer — field investigations, tactile experiments and guided movement activities work best.

When reporting outcomes from nature interventions, follow rigorous reporting practices. Include pre/post means and standard deviations, effect sizes such as Cohen’s d, sample sizes and p-values from the source study. That makes results comparable across classrooms and studies. Typical short‑exposure research uses within‑subject or randomized designs and shows improved attention or working memory after nature exposure versus urban or indoor controls; Berman et al. (2008) is a clear example using randomized exposure and pre/post working memory testing.

We, at the Young Explorers Club, link these practices to our outdoor learning approach and embed short restorative walks plus longer multisensory lessons into schedules so kids return to tasks with sharper focus and more durable memories. Learn more about how this works by reading our outdoor learning overview.

Mental health, stress reduction, ADHD and behavioral outcomes

We, at the Young Explorers Club, prioritize green-time because it produces clear mental-health benefits. Systematic reviews (Bowler et al. 2010) report that even short visits to green space reduce heart rate, lower blood pressure and cut self-reported stress. The evidence base includes randomized, within-subject and quasi-experimental studies that point in the same direction: nature lowers physiological stress markers and subjective tension.

Evidence and practical effects

Forest-school evaluations and other nature-based learning studies report better mood, higher self-esteem, reduced anxiety and improved emotional regulation in children and adolescents. Those programs show consistent pre/post gains on wellbeing scales and teacher observations of emotional control. Taylor, Kuo & Sullivan (2001) found that children with attention‑deficit symptoms concentrated better on post-activity tests after walks or play in green settings than after comparable urban play. Other work links increased outdoor green time with lower ADHD symptom scores, and many studies use within-subject comparisons to strengthen causal claims.

Outdoor lessons also improve classroom behaviour. I often see fewer behavioural incidents after an outdoor session and higher on-task levels in the following indoor lessons. Programs that mix active outdoor learning with short reflective periods tend to yield the largest gains in attention and self-regulation. Forest‑school style programs, specifically, produce measurable improvements in emotional regulation and self‑esteem when assessed with teacher ratings and child self-reports.

Measurement and evaluation

To evaluate mental-health and behavioural outcomes I recommend the following measures and designs:

- Collect physiological markers: heart rate, blood pressure and salivary cortisol for stress response.

- Use validated self-report wellbeing scales for mood, anxiety and self‑esteem.

- Obtain teacher ratings of behaviour and attention using standardized checklists.

- Track incident and discipline records to quantify behavioural shifts.

- For forest‑school programs, add pre/post self-report scales plus structured teacher observations.

- Prefer within-subject or randomized crossover designs where feasible; report effect directions and magnitudes (for example, mean reductions in heart rate or blood pressure and changes in scale scores).

- Present both statistical significance and practical effect sizes so stakeholders see real-world impact.

We design our sessions and assessments so results are actionable for teachers, parents and program funders. Read more about our approach to outdoor learning to align evaluation with practice.

Academic performance, engagement, motivation and social‑emotional learning

We, at the Young Explorers Club, base our practice on synthesis reviews that find clear positives for personal and social development and suggest gains in subject learning—especially science and environmental topics (Rickinson et al., 2004; Natural England evaluations). We also recognize those reviews flag variable effect sizes and study designs, so we report sample sizes, effect sizes and limitations whenever we share outcomes (Rickinson et al., 2004; Natural England evaluations).

We see a reliable chain of mechanisms in action. The outdoor context increases engagement and motivation. That heightened attention drives deeper processing and richer, contextualized encoding. Students then retain concepts longer and transfer learning to new problems, which can translate into long‑term attainment gains.

We match pedagogy to setting. Inquiry‑based science lessons map naturally to outdoor tasks. Place‑based literacy lessons bring texts to life. Measurement‑based math works when students collect and analyze real data. Project learning and art flourish with natural materials and varied sensory input. I recommend linking curriculum aims directly to authentic outdoor tasks so learning stays rigorous and measurable. Learn more about why outdoor learning works in practice.

Practical measurement and classroom fit

We recommend using these complementary measures to make claims robust and useful:

- Topic‑specific pre/post academic tests tied to learning objectives.

- Transfer tasks that assess application in novel contexts.

- Teacher and student engagement surveys, including percent reporting “I enjoyed this lesson.”

- SEL scales for confidence, teamwork and resilience.

- Observational rubrics for collaboration and leadership during projects.

- Longitudinal tracking where feasible to detect sustained attainment changes.

We also test at the design stage. We aim for adequate sample sizes and include control or comparison groups when possible. We compute and report effect sizes and confidence intervals. We document fidelity: how the session was run, weather, group size and instructor moves. That transparency helps others interpret variable findings in the literature (Rickinson et al., 2004; Natural England evaluations).

We design lessons so assessment and instruction reinforce each other. Short cycles of data collection, reflection and reteaching keep engagement high and let us refine tasks for clearer academic gains. We train teachers in inquiry facilitation and simple measurement techniques so outdoor lessons stay efficient and repeatable.

Physical activity, health and cognitive links

We, at the Young Explorers Club, see kids move far more outdoors than inside. We design our outdoor learning to extend activity levels beyond what classrooms deliver. Children show higher step counts and greater minutes of moderate‑to‑vigorous physical activity (MVPA) during outdoor lessons and play compared with indoor equivalents; outdoor free play can roughly double step counts relative to indoor free play.

Higher daily physical activity matters for thinking and school success. Greater MVPA and less sedentary time are linked to better executive function, including improved attention, working memory and cognitive flexibility, and to stronger academic outcomes. We pair active sessions with brief focus tasks and see attention and task persistence improve immediately after outdoor activity. Reducing sitting time also supports physical health and classroom readiness.

I recommend integrating short active segments inside lesson plans and structuring larger chunks of time outdoors so kids hit meaningful MVPA each day. We track activity objectively and connect those measures to learning outcomes to test whether physical activity drives cognitive gains. Presenting activity and academic data together helps reveal mediation pathways: physical activity → cognition → attainment.

Measurement and reporting

Use the following when running programs:

- Use pedometers or accelerometers to record mean steps per lesson.

- Record mean minutes MVPA per lesson.

- Calculate percent of lesson time sedentary versus active.

- Report group means and standard deviations, and compare indoor versus outdoor lessons.

- Present minutes of MVPA per session and average steps per lesson alongside academic and attention outcomes to explore mediation pathways (physical activity → cognition → attainment).

Making outdoor lessons work: frequency, lesson design, tools, measurement, safety and evidence caveats

We set clear frequency targets first. We aim to meet or exceed the 120 minutes/week wellbeing benchmark (White et al. 2019). Short nature breaks of 20–30 minutes restore directed attention quickly, while 30–60 minute lessons let students engage in richer multisensory learning. Practical schedules that work in schools include:

- two 60‑minute outdoor lessons per week for deep investigations,

- four 30‑minute sessions to balance attention restoration and curriculum time,

- or daily 20–30 minute nature breaks to improve focus and mood.

We recommend piloting changes before scaling them. Run an 8–12 week pilot with matched classrooms or randomized groups where possible. Collect baseline and follow‑up data to judge impact and refine the approach.

Pilot design and recommended metrics

- Pilot length: 8–12 weeks, with matched classrooms or randomization to reduce selection bias.

- Core data to collect at baseline and follow‑up:

- attendance,

- disciplinary incidents,

- teacher‑rated on‑task behavior,

- topic‑specific pre/post tests,

- student wellbeing scales, and

- physical activity via pedometer/accelerometer.

- Evaluation metrics to report: academic test deltas, percent on‑task, minutes of MVPA per lesson, mean steps/lesson, wellbeing scale scores, plus qualitative teacher and student feedback.

- Reporting standards: preregister protocols where possible and always report sample sizes, effect sizes and limitations to help others interpret results.

We promote proven programs and simple kit to get lessons running on day one. Consider Forest School principles, Outdoor Classroom Day and Project Learning Tree for structured curricula, and the John Muir Award for longer projects. Use citizen‑science apps such as iNaturalist, Seek and Merlin Bird ID alongside data tools like Epicollect5 to capture observations and build assessment records. Pack basic equipment:

- clipboards,

- waterproof notebooks,

- hand lenses,

- measuring tapes,

- thermometers,

- a first‑aid kit and

- suitable clothing for the season.

We point teachers to concise primers on outdoor learning to jumpstart lesson planning.

We design lessons with curriculum alignment in mind so outdoor time counts toward standards. Lesson types that translate well include:

- inquiry‑based science investigations that use local habitats,

- place‑based literacy where texts connect to the site,

- math outdoors using measurement and navigation,

- art projects that use natural materials,

- PE and outdoor sports focused on perseverance and coordination,

- long‑term projects that track seasonal change.

We address common barriers pragmatically. For risk‑averse policies, use risk‑benefit assessments and clear emergency procedures so leaders feel secure. For staff confidence, provide short training sessions and co‑teaching pairings so novice teachers learn on the job. For weather and logistics, plan seasonally and use school grounds to avoid travel delays. For curriculum time pressure, integrate outdoor tasks with learning objectives so lessons serve both wellbeing and attainment goals.

We interpret evidence cautiously and ask for rigorous evaluation. Many positive reports exist but study quality varies; systematic reviews such as Rickinson et al. 2004 call for more randomized controlled trials, standardized outcome measures and consistent reporting of effect sizes. Address likely confounders in evaluations: novelty effects, teacher enthusiasm, selection bias and baseline differences between groups. We recommend preregistering evaluations, including control conditions where feasible, and transparently reporting limitations so results are useful to other practitioners.

Sources

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency — The Inside Story: A Guide to Indoor Air Quality

UK Government / Natural England — Natural Connections Demonstration Project: evaluation reports

Forest School Association — What is Forest School?

Outdoor Classroom Day — About Outdoor Classroom Day

Project Learning Tree — Environmental education resources for teachers

John Muir Award — About the John Muir Award

iNaturalist — iNaturalist: help identify the plants and animals around you